The return of "The Watchman"

In a joint enterprise between writer and musician Hana Gubenko and myself, Samuel Taylor-Coleridge's short-lived political journal The Watchman returns in a new guise, as an internet magazine designed to stimulate and inform.

Here, in our first issue, we present four articles: an Editorial, a book review, a podcast around the music of Hans Winterberg and Entartete Musik between myself, Hana Gubenko, Frank Harders-Wuthenow and Dr Michael Haas (originally released Sunday, July 14), plus a review by myself of the first performance of Hans Winterberg's 1926 String Quartet at the Großer Salon of the Schwartzsche Villa, Berlin, presented by the Amadello String Quartet (comprised of members of the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin), Holger Groschopp (piano) and with readings by novelist Jaroslav Rudiš from his book Winterberg's Last Journey.

Contents:

Editorial: Pantisocracy Para Siempre, or let's give The Watchman another go! (immediately below)

Article about Hans Winterberg, The Mission of Fascism

Book review, Remember My Childhood by Itka Frajman Zigmuntowicz

Concert review from Berlin, Winterberg & Winterberg at Berlin's Schwartzsche Villa

Editorial:

Pantisocracy Para Siempre, or let’s give The Watchman another go!

¨All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others¨(George Orwell, 1903-1950)

‘Pantisocracy’ is dealing mostly with reasonable equality between individuals. The kind of equality which does not void the uniqueness of individuals, but instead builds bridges between them. Everyone feels differently, we all see the world with different eyes, which means that the world and its affairs is built up into an entirely unique image for every individual. The question is, how do we discern the true image from the false one?

The answer is not easy; but is not that complicated either. To see clearly, we must use a prism comprised of sanity, critical perception, and abundant empathy. We have an obligation to leave aside our ingrained prejudices, and look at our surroundings with the openness of an independent and unbiased mind to gain a proper overview (and wisdom). As a society, we’ve got a lot to think about, and to contemplate. Possibly, we need to reassess some well-established views and try for clarity if the remainder of human civilisation desires to move ahead. Take the recent pandemic, when suddenly, in the blink of an eye, we became quite Darwinist . As Western European society, we like to preach democracy and tolerance, but suddenly we’ve been dealing with the questions of who is worthy of life, and whether our pleasure should be sacrificed in favour of others’ safety. We were confronted face-to-face with questions which we were eager to avoid, such as: Is it worth it to see our grandchildren once again, to be spending time together with our friends and family, or is it better staying safe at home, locked down.

Social frames are far more effective than barbed wire. They give us the illusion of affiliation, but it is only an illusion. Whilst stuck inside those frames, we believe we have Free Will, but if we stay inside of a certain mind-framing, we can’t be independent and detached from the well-established preconceptions of our social environment with roots far back into the past. Those frames are serving both as a doom and as a blessing. “Doom” because we are convinced that we follow our own choices, but are we actually free to do so, or rather are we just in the flow of a pre-destined genetic program, its path chosen by our genealogical tree? Most probably, we are as free as we are not, because we deal with life through deeply rooted ancestral codes. The blessing lies in freedom to acknowledge the impact of inherited beliefs on our personal perception, to observe, to re-think, and re- adjust our patterns. When doing so we might arrive at a detached decision, we can remain connected to our history and social environment, but as independent thinking individuals we even might gain the courage to change the “pre-ordained” paths for the better. In fact, the only freedom we do have is either to decide to follow a pre-determined path, or to break free; to be our actual selves, or to remain a semi-conscious executant of genetic programs which are in danger of being misused by questionable policies. Assuredly, we have the choice to grow further, beyond the frames of predestination caused frequently by the preconceptions of our environment; we have the freedom to explore the world with own pair of eyes and ears. We can observe, we are in charge. It’s up to us to choose if we are willing to remain in a herd mentality, or whether we want to reach a state of conscious freedom from prejudices which might prevent us enjoying our being.

The everlasting question as to whether the truth is an objective, or a relative value is not that hard to answer. Life gives strict indications to identify the truth and to discern the real from the fake. We need to watch, we need to hear, and to properly distinguish. To do so, we might require help. That help is, specifically journalism, the help of an independent source which watches connections and (in our case) through the prism of arts because art reflects social tendencies and gives us a clear picture what is about to emerge. This reflection gives us a chance to be prepared to deal with the forthcoming issues in a timely fashion. By carefully examining the tendencies which are unmistakably gleaming through art, we gain the opportunity to choose a better path, to save what can be saved, and be prepared for changes. By watching the connections to the past and honouring our roots, we can improve the future and remain an open-minded and progressive civilization.

All of this is why we want to give The Watchman another go. Initially founded by Samuel Taylor Coleridge back in 1796; Coleridge’s virtuous creed was to embrace the liberating word of truth. We are ambitious to embrace it once again, this time with the humility of a non-judgemental stance via the critically-oriented words of art critics. We are at art’s service and at the service of our audience by reviewing, and by interviewing; we are empowered to see art in context of social deployments and to read between the lines. Therefore, we are exploring art and watching the connections. Let us take up the mission again, let’s try to keep the spirit of equality alive if not para siempre, then just in the here and now despite the fact that, alas, some will certainly remain more equal than the others!

Hana Gubenko & Colin Clarke - Publishers

The mission of fascism ...

... is the extinction of humanness but, to our joy, that mission failed, and legacies are re-emerging for civilisation’s sake.

Let’s dive into the question of what does Fascism want? It wants to over force the low of Creation and to establish own. All sacrifices justified by drive to build envisioned world by certain human beings destroying the natural order of things, which was established long before the time when human beings emerged to tame the earth and all the living.

Fascism raises its hand over the Creation and gives oneself permission to decide about the worth of life, which tribes to cultivate, and which shall be truncated and utilised. The definition of their worth is based on questionable convictions, which seem to be enrooted in the long-held inferiority complexes. The extinction of the genotype and of cultural assets is the primary attitude of any strike of fascism.

Let’s think of human gassings, Dr. Mengele’s sterilisations in order to prevent subhuman’s genotype to spread the roots and on the other hand the burning of the books and prohibition of degenerate music (“Entartete Musik”). This resulted in the breaking of the flow of cultural inheritance and interrupted natural exchange and the diversity. Art and music have pivotal roles in the social environment, and the oppression of composers was one attempt to trim society by the establishment of the Nazi era.

One example is Czech-German composer Hans Winterberg. Born in Prague in 1901 into a Jewish family, Hans Winterberg was taught by leading figures of the classical music scene of that time like Fidelio Finke, Alexander Zemlinsky and Alois Hába. Winterberg explored multiple facets of music and engaged in various genres. Besides composition he worked as a vocal coach and repetiteur in several opera houses and musical ensembles. Most probably because of such profound and multi-layered musical experiences, he formed an independent style. His music is traditionally-rooted: one hears the influences of Impressionism, Wagner and Richard Strauss as well as connections to famous contemporaries like Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Bartók and the Second Viennese School. And yet, he brings his very own signature by skillfully combining clear counterpoint with modern orchestration. His music demonstrates a rare example of balance between tradition and the innovation. Hans Winterberg could be as famous as Prokofiev or Stravinsky were it not the occupation of the German Wehrmacht, and his subsequent deportation to the Theresienstadt Ghetto in January 1945 would make his life to dust as was the case for millions of other lives. His luck was a timely liberation on the eighth of May 1945.

After two years in Prague, Hans Winterberg emigrated to Germany. He followed his “Aryan” wife Maria Maschat and their common daughter Ruth who had been expelled from the Czechoslovakian Republic following the Beneš-decrees in 1946. He didn't see a future for himself in a communist Czechoslovakia, as he wrote many years later to his compatriot Rafael Kubelík.

Hans Winterberg was eager to embrace his work and make it known, but a silly twist of fate has made his efforts void. After his death, Winterberg’s manuscripts have been sold to the Sudeten German Music Institute in Regensburg and locked for publishing and for performance due to a bizarre contractual agreement . According to that particular agreement, the composer’s musical estate was to stay under embargo until December 2030, but luckily the “Mission of Extinction” failed not only globally, but here too, and thanks to the composer’s grandson Peter Kreitmeier and the Exilarte Research Centre in Vienna under the lead of Dr. Michael Haas, Winterberg’s music has been liberated, and in co-operation with world-leading music publisher Boosey & Hawkes, published and recorded.

Thanks to the determined deputies of cultural inheritance as Dr. Michael Haas and Frank Harders, Hans Winterberg’s legacy has been not only saved, but it receives a chance to flourish and to conquer the audiences of today with the prospect of regaining a future. Hans Winterberg is not alone on the list of Frank Harders, who is untiringly engaged in saving and enlivening music of composers, whose lives and work succumbed under the fascistic mission of extinction. We certainly can say the mission to withhold Winterberg's music failed thanks to devoted work and the zeal of people whose mission is to save our cultural inheritance for the sake of our civilisation and for the preservation of the humaneness within.

On 12 of July, we attended the first performance of the string quartet no. 1 by Hans Winterberg along with other pieces at the Schwartzsche Villa in Berlin. Colin Clarke as Classical Explorer has been in place and prepared report to share on www.classicalexplorer.com (see below), and on the 14 of July, we are pleased to announce the very first episode of our podcast The Watchman in conversation with Frank Harders and Dr. Michael Haas as our guests was published on our YouTube and Spotify channels.

Do stay with us and we will keep you posted!

Hana Gubenko

Some useful links:

Hans Winterberg at the Boosey & Hawkes website

Hans Winterberg's Wikipedia entry

Article on the Boosey & Hawkes website: Rediscovering Winterberg: a composer hidden by history

Another article, an introduction on the Boosey & Hawkes website, In the Labyrinth of Identities by Michael Haas

Exilarte: Zentrum für verfolgte Musik, research centre for “Banned Music,” which in 2016 was incorporated into the Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien (website in English)

From Michael Haas' website Forbidden Music, an extended article with sound samples and many illustrations: The Winterberg Puzzle's Lighter and Darker Shades

Publications of Frank Harders-Wuthenow at Schott publishers

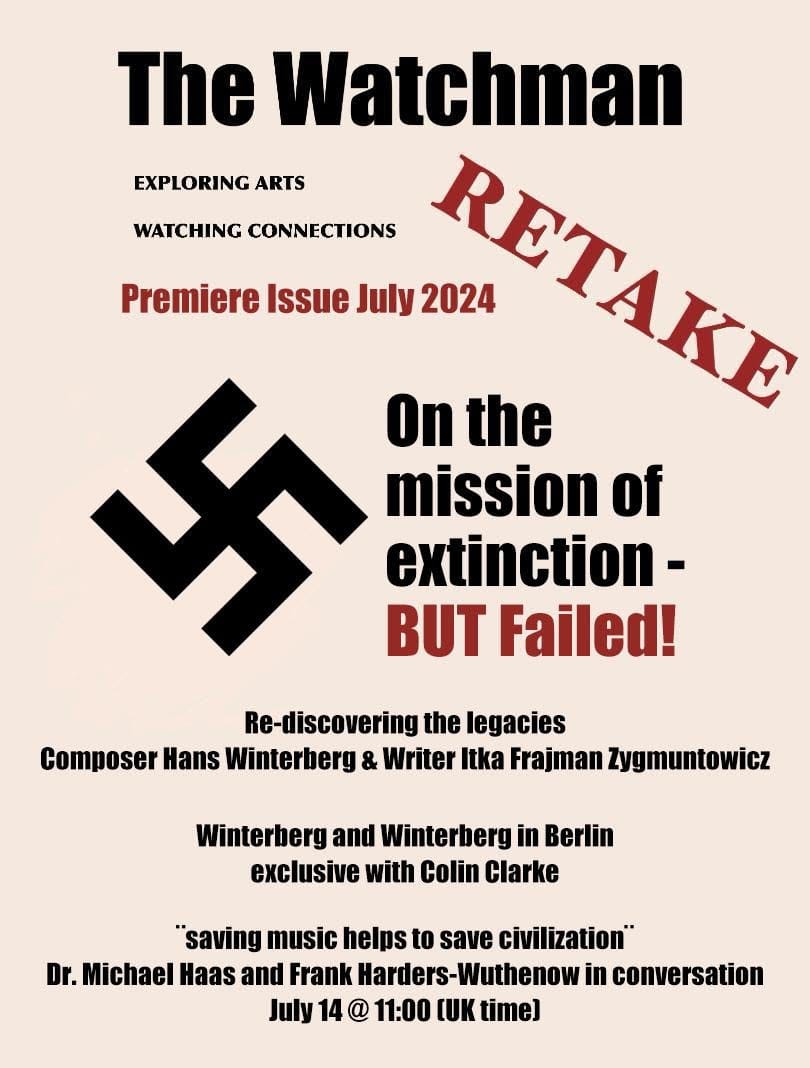

Book Review:

Remember, My Child by Itka Frajman Zygmuntowicz

“No Flowers Grew in Aushwitz,¨ BUT “Les fleurs du mal¨

Just like a leaf tossed to the wind

Separated from its branch and tree

Not belonging any more

Liberated but not free.

Carrying the pain of separation

Memories of a world that used to be

A world that is no longer here.

I still see the Sabbath candles

And my mother’s gentle face

My Father chanting the prayers

And my grandmother in her white shawl of lace.

I see my little brother and sister

So young and so full of cheer

Not yet understanding prejudice and hatred

But sensing uncertainty and fear.

The Nazi boots are marching

My world with terror filled

The Holy Scriptures burning

Children starved, tortured and killed.

The ghettos closing us in

What could possibly be in store?

My world grows smaller and smaller.

Nothing is like it was before.

The freight trains are taking us on journey

For most it is their last ride

My brothers and sisters are burning

There are no more places to hide.

Hitler’s final solution I sealed

Trapping my family in a world of hell

I am that I have survived

The story of the Holocaust to tell.

Itka Frajman Zygmuntowicz (1926-2020)

There are so many brilliant and famous films made about the disgraceful crimes of Nazi era and the unbearable legacy of the Holocaust. Just think of Schindler’s List by Spielberg and Polanski’s The Pianist, or the heart-wrenching La raffle by Roselyn Bosch. Those marvellous films are showing us unimaginable images of the human abyss on the screen, but they aren’t witnessings: they are pieces of Art.

The writer and Holocaust-survivor Itka Frajman Zigmuntowicz bears witness from her heart directly to the heart of reader through her sophisticated, poetic words. Those words could be full of bitterness and pain, but instead they are fulfilled with love and dedication in her book Remember, My Child published in 2016.

Like so many other victims’ dreams of life that have been destroyed by Nazi’s deadly vision of superiority, Itka’s early dream to get a formal education and become a writer was smashed into smithereens under the Gestapo’s boots. But the deadly mission of Fascism to erase the lives and bring extinction failed. Itka lost her family, her world, her homeland, but she herself has survived the Camp of Death the Auschwitz -Birkenau.

She marched the Death March from the gates of Hell into life, to spread her roots, to tell her story and the story of millions of others whose voice has been silenced within Zyklon-B behind electric barbed wire.

That was tough luck for the Nazis but our blessing, that she has made it through! She got most painful education from history itself, despite all twists of life, she’s built a mosaic out of those slivers of her early dream by putting each of them together with a glue of love, compassion and forgiveness. Itka Frajman Zygmuntowicz became an exceptionally gifted writer. The book Remember , My Child bears more than a testimony of a survivor, it makes it clear why is it worth staying alive and to go on, when even one is urged to go through Hell without navigation or a guiding light at the end of the dark tunnel of despair and pain. She says :

Only the person who thinks with her own mind is free; one who makes her own choices and doesn’t follow others...

Herewith we are back at the beginning of this Issue of our Watchman.

In fact, we can be free and solitary if we think with our own mind. To keep that mind sharp, we need the navigation mechanism of books, which can be as holy scriptures, but also books, which bear the light of truth. This light glimmers trough Itka’s verses, so artfully interweaved with threads of eternal wisdom

Every human word and deed

Gets inscribed in the eternity of time

And long after we are gone

Do all our words and deeds

Still affect the lives of those

Whom we have touched

And link themselves together

To the long human chain of eternity ( 1944)

In the final analysis, the fairy lights made out of words of truth are the only way to illuminate the prickly way out of Hell into life.

The book Remember, My Child as well as other works by Itka Frajman Zygmuntowicz is available on Amazon.

Review by Hana Gubenko

The book may be purchased at Amazon here.

Concert Review:

Winterberg & Winterberg at Berlin's Schwartzsche Villa

Winterberg & Winterberg: An encounter of music and literature Jaroslav Rudiš (reader); Adamello Quartet (Clemens Linder, Byol Kang, violins; Susanne Linder, viola; Adele Bitter, cello) with Holder Groschopp (piano). Schwartzsche Villa, Grünewaldstraße, Berlin, 12.07.2024

Hans Winterberg (1901-1991) Sudeten-Suite (“Errinerung an die Sudeten”). Cello Sonata. String Quartet No. 1 (Symphony for String Quartet, World Premiere)

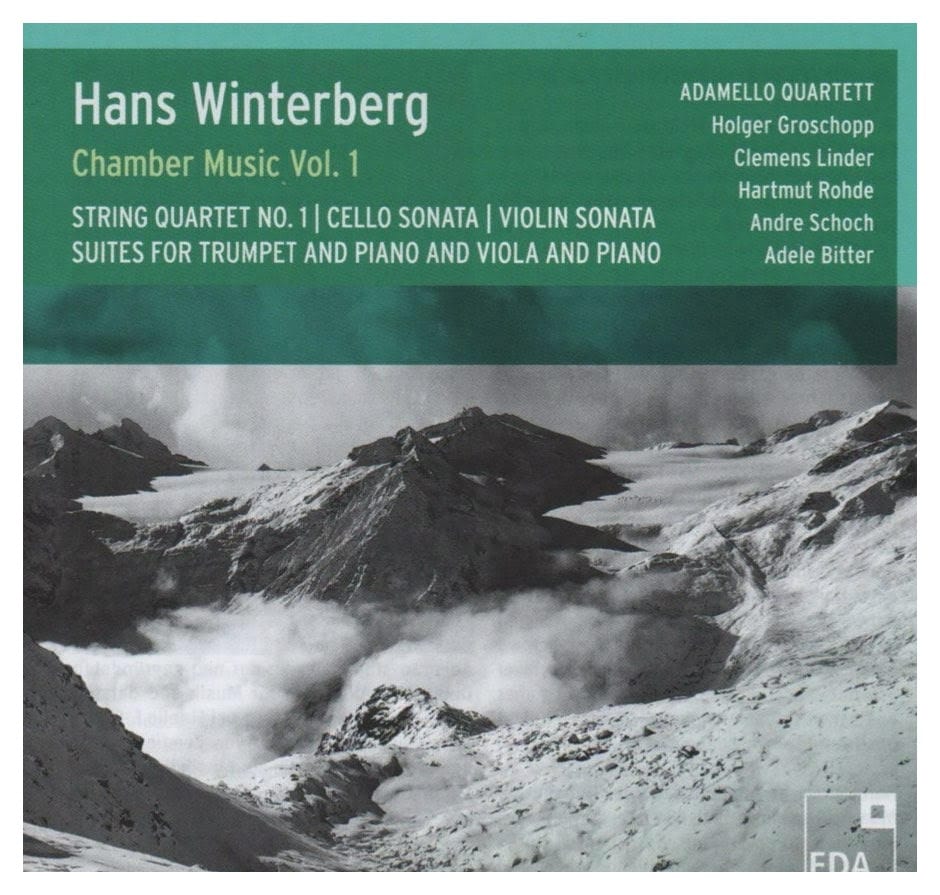

The brainchild of Frank Harders-Wuthenow, this concert celebrated the music of Hans Winterberg (1901-1991), while coinciding with the release of the first volume of that composer’s chamber music on the EDA label: the Cello Sonata and the String Quartet No. 1 appear on the disc, supplemented there by the Trumpet Sonata No. 1, the Sonata for Violin and Piano and the Suite for Viola and Piano.

For more on the activities of Frank Harders-Wuthenow, and more on Hans Winterberg and Entartete Musik, I recommend a podcast featuring Harders-Wuthenow, Dr Michael Haas, hosted by Hana Gubenko and myself shown above: for convenience, the Spotify link is here. Also present at the concert was the composer’s grandson, Peter Kreitmeir, who has played a key part in the liberation of Winterberg’s manuscripts.

There is more here than Hans Winterberg, though. Why Winterberg & Winterberg? Who is the other?. The one who is ‘not Hans’ is Wenzel Winterberg, the protagonist of a superb novel by Jaroslav Rudiš, Winterberg's Last Journey. Czech-born Rudiš wrote the book in German, but it is available in a brilliant translation by Kris Best here (Best was also at the event). Readings were obviously in German. Although not the same Winterberg, there ae parallels, not least in the ‘musical’ nature of Rudiś's book, including a Leitmotif that runs through the book that refers, poignantly and unforgettably, to a

beautiful landscape of battlefields, cemeteries, and ruins...

The Schwzartzsche Villa is itself a beautiful setting just outside the centre of Berlin (it also hosts exhibitions, currently Michelle Jezierski’s Verge). The core ensemble of the Winterberg concert was the Adamello String Quartet, comprised of members from the DSO (Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin) with one tweak: second violinist Nikolaus Kneser was replaced by a concert master of the DSO, Byol Kang.

The whole was prefaced by a pre-concert talk delivered with intensity and passion by Harders-Wuthenow. The space is small, but it was packed: there is clearly an appetite for the new in Berlin, reflected perhaps also in the enthusiastic reception.

Here on The Watchman we have our own introduction in the form of a sequence of video interviews made by myself both prior to and after the event. This includes introductions by Peter Kreitmeir, (Winterberg's grandson), Frank Harders-Wuthonow of Boosey & Hawkes, novelist Jaroslav Rudiš, Katja Kaiser of exil.arte, Clemes Linder, first violinist of the Adamello Quartet, and two audience members: Lukas Kowalski, who is also the producer of the upcoming recording, and one very characterful gentleman audience member who kindly and enthusiastically gave his time. All of these can be found by clicking here.

It was the intersection of words and music in the main body of the concert that was so special. First, Rudiš read from the very beginning, the chapter “From Königgrätz to Sadowa” (pp.13-20 of the English edition). The reading brought out the idea of text almost as music: word repetitions (as well as that literary Leitmotif) took on sonic significance.

Around this reading, we heard Hans Winterberg’s Sudeten-Suite (Memories of the Sudeten), composed in 1963/4. The idea of memories, of a Rückblick, is enshrined in Winterberg’s traditional harmonic language here in this ten-minute piece for piano trio. The pianist was Holger Groschopp, known for his associations with the Berliner Philhamoniker and the DSO as well as his recording of the complete piano music by Simon Laks on the Cybele label and his recordings of Busoni transcriptions on Capriccio. Elements of Dvořák were certainly present in the Winterberg, in a piece of great freedom. Maybe there was a hint of Janáček over the central ‘Rund um den Plöckstein", a place of expansive violin lines set against sudden juxtapositions. On has to admire Groschopp's playing in the finale, "Elbe-Quellen," a difficult piece that nevertheless exudes a happy, open-air demeanour and some remarkably fresh counterpoint.

Another reading – now the chapter ‘From Jičín to Budweis' (pp. 167-169, Wenzel Winterberg’s memories of Prague) and then, ‘From Budweis to Winterberg’ (pp. 179-186) before the Cello Sonata (1951). This sonata has been recorded by the present performers, Adele Bitter and Holger Groschopp, on the upcoming EDA disc of Winterberg's chamber music. The Cello Sonata is a short work of only around 13 minutes, but its three movements contain the kernel of Winterberg’s style. There is a neoclassical aspect here, but there is also a sense of urgency. This last is particularly audible in the first movement, almost breathless and yet bursting with ideas. The textural differentiation Winterberg clearly uses was highlight by the performers, particularly via Groschopp’s variety of tone. In comparison with the Sudeten-Suite, the musical language is suddenly much more advanced; the difficulty of the individual parts increases exponentially. Adele Bitter’s staccato and clear rhythmic mastery gave the cello part much life. The piano’s active descending theme had a touch more of the special about it, a sense of discovery, in the live performance than it does on the EDA disc, incidentally.

The central ’Mit ausdrucksstarker Bewegung’ is a shadowy song without words. The piano begins with delicate high chords against which the cello, lower, sings. This is a Nocturne like no other. As recording engineer and ‘Entartete Musik’ expert Michael Haas has suggested, shadows are deep here, and Bitter and Groschopp captured the music’s interior heart perfectly; the audience was enraptured, and rightly so. The finale begins with a cello repeated note that can only be described as ‘buzzing’ before the piano embarks on a twisted ragtime whirligig, a wild folk dance; If that sounds like a whole lot of twisted fun, it is. The sense of abandon exuded by Bitter and Groschopp was immense.

Another reading: a pair, in fact. ‘St. Anne’s’ (a hospital in Brno after a heart attack, from p.311) and from the penultimate ‘The Storm’ (pp. 427-431). Then ...

It is quite a thing to experience the World Premiere of a piece written in 1936, but that was the case here with Hans Winterberg’s First String Quartet.

The String Quartet No. 1 is one of Winterberg’s most complex works of his pre-war period. It has been said the piece sits somewhere between Janáček and Pavel Haas on the one hand, and the works of the Second Viennese School (Schönberg, Berg, Webern) on the other. Rhythm and motifs take on equal significance in Winterberg’s remarkable sonic tapestry. There are three movements (Allegretto; Molto tranquillo; Allegro vivace), but they emerge as one complete whole, or at least they did in this remarkable performance. The third section takes up material form the first, with the central Molto tranquillo nicely delineated in structural terms.

The subtitle is ‘Symphony for String Quartet’ and the piece is indeed linked to Winterberg’s First Symphony via its ‘disguised’ formal scheme: three movements heard as one.

The Quartet begins quietly, on second violin, an oscillating figure that worries, its rhythmic distortions implying an undercurrent of ungroundedness. The soundworld is unique, but if I had to single out one point of reference it would be Zemlinsky; and yet there are mechanistic passages that take us into altogether different regions against which melodies strive to emerge and gain freedom. Repetition of small cells is another component of Winterberg’s vocabulary; the Adamello Quartet played superbly, allowing textures to speak naturally, projecting maximal clarity throughout and above all squeezing every dop of expressive juice from Winterberg’s complex, rewarding score.

The Molto tranquillo features a violin song (Clemens Linder truly touching) against an almost whispered, unsettlingly mobile background; perhaps that ‘tranquillo’ should come with a qualifier; or perhaps his was Winterberg‘s definition of tranquility!. The musical language here is truly individual, the performance unforgettable. The movement’s final place of repose is interrupted by melodic shards in repetition. The writing for quartet is truly wondrous here, as it is in the music’s later interiorisation. Winterberg writes with true independence of line for all four instruments, coming together into a wonderfully inventive whole. There are moments in this finale that require the utmost control of musicians over their instruments, not least the poignant close, which hangs in the air; one could not have asked for more from the Adamello Quartet.

For those interested in exploring the music of Hans Winterberg further, the next logical stop might be a recording on Toccata Classics of String Quartets Nos. 2-4 by the Amernet Quartet (TOCC 0683) and a twofer on Pierian (0054/55) which contains Symphonies Nos. 1 and 2, the Ballade um Pandora, the Symphonischer Epilog, the Symphonische Reiseballade, and Stationen. Lovers of wind music might enjoy another Toccata release (TOCC 491) which includes the Suite for Flute, Oboe, Bassoon and Harpsichord, the Suite for Clarinet and Piano, the Cello Sonata (there played by Theodore Buchholz and Alexander Tentser), the Wind Quintet and another Suite, this time for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon and piano.

Even more excitingly ...

The EDA label will release Hans Winterberg, Chamber Music, Volume 1 on September 6, 2024. Copies were available at the concert, and I am lucky enough to own one. All compositions on that disc were newly edited from the manuscripts for this recording in co-operation between the Exilarte Research Centre of the Vienna University of Music and the international music publisher Boosey & Hawkes.

Further chamber music recordings and the complete works for piano with pianist

Jonathan Powell will follow.

The programme of the EDA disc is as follows:

String Quartet No. 1 “Symfonie für Streichquartett” (1936), Sonata for Violin and Piano (1942), Suite for Trumpet and Piano No. 1 (1945), Suite for Viola and Piano (1948/49), Sonata for Cello and Piano (1951)

Performers: Adamello Quartett. Adele Bitter, cello. Holger Groschopp, piano. Clemens Linder, violin, plus

Hartmut Rohde, viola. Andre Schoch, trumpet

The Cello Sonata and the First String Quartet were performed in the concert above. Although a review will not be posted on Classical Explorer until release (plus, in The Watchman's next issue), I can tell you now that many, many delights are in store. The Viola Sonata contains passages of unutterable beauty in its slow movement, the Trumpet Suite is fascinating in its playful use of its solo instrument, while the Violin Sonata enjoys a brilliant performance by Christian Linder (who has the most amazing violin sound) and pianist Holger Groschopp.

Colin Clarke

Some further useful links:

This website of the Steglitz-Zahlendorf area of Berlin contains much information about Schwartzsche Villa

Website of the Adamello String Quartet

Jaroslav Rudiš' entry at the Czech Literary Centre website

Peter Kreitmeir's website (Peter is also a goldsmith, so scroll down for the music part)

My review of the Berlin concert as it appears on the Seen and Heard International website, Berlin Celebrates the music of Hans Winterberg