Two fine young singers: Elgan Llŷr Thomas and Alexandra Lowe

Two fabulous discs - fill your boots!

This post is a fine opportunity to explore the talents of two young singers. We start with Welsh-born tenor Elgan Llŷr Thomas, a singer who I have already encountered in a number of roles: as Normanno in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor at ENO in 2018 (review); as Johnny Inkslinger in ENO’s Alexandra Palace performance of Britten’s Paul Bunyan the following year (review); he was also “First Follower of Telramund” in the Royal Opera’s Lohengrin last year (review). It is good to have him full-focus in this disc: his voice is strong and yet haunting - perfect, certainly, for the Brtten on his disc, Unveiled.

Thomas has already established himself as a modern representative for young, queer singers, performing on some of the most iconic stages across the UK and beyond. The disc Unveiled was released for Pride month and is a musical tale of queer British culture from the 20th Century to the modern day. Thomas, as a gay musician and composer, became increasingly frustrated by opera’s traditional focus on heterosexual relationships and resolved to find more LGBTQ+ representation in vocal music. To achieve this, he has crafted an album that sheds new light on works from the UK’s most iconic gay composers and poets alongside music by typically marginalised artists.

Here’s a video about this disc:

For this project, Thomas specially commissioned theatre director, lyricist and translator Jeremy Sams to write a brand-new English translation of the songs to highlight their deeply intimate meaning and make plain the romantic nature of Pears and Britten’s connection.

Thomas is joined by pianist Iain Burnside,a terrifically experienced pianistic collaborator in song. The Michelangelo cycle was premiered orignally by Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten themselves, at London's Wigmore Hall, in September 1942. Michelangelo's love poetry was directed at the nobleman, Tommaso Cavalieri. The premiere was a full quarter-century before homosexuality was legalised in England and Wales.

Thomas sings with great power (listen to the cry at the words, “I have been imprisoned like a knight in armour” from Sonnet XXXI). He also has a Peter Pears-like ability to project not only the perfect diction but also the perfect meaning of every word. Good, then, to have this sung in Sams’ excellent translation.Listen to the power of the second song. Thomas’ high register is sweet and yet plangent, a perfect combination. The intensity of Britten’s lines is delivered with tensile strength; the jittery anxiety of Sonetto XXXII (the penultimate movement) is palpable, Burnside’s staccato the supreme vehicle for the song’s nervous energy.

The C sharp-Minor of that penultimate song resolves onto the D -Major of the final “Sonetto XXIV,” powerfully potent in its solo (unaccompanied) line and quietly muscular piano As the longest song of the cycle, it seems to contains worlds - worlds of anguish (“I am lost in a maze of blind devotion ... That cruel Fate could shatter such consciousness - / That Death may lay a finger on such sweetness”).

This is an astonishingly powerful performance, and I can pay it no higher compliment than to report that on finishing auditioning, I played it again, straight away. Of course Pears and Britten have an authority here, but Llŷr Thomas and Burnside offer a performance for our times. Here, though, are two videos (the performance is split) of Pears and Britten from Japanese television, February 9, 1956:

It is fascinating to hear more music by Ruth Gipps (1921-1999). Horn players will doubtless know her Concerto for that instrument from 1968 (here’s a YouTube video of David Pyatt on the Lyrita label), and I would definitely recommend listening to her excellent Second Symphony there’s a Chandos recording, but also this one conducted by Douglas Bostock. Her settings of bisexual poet Sir Rupert Brooke, Four Songs of Youth, are next on Unveiled. Gipps has her own musical language, initially English Pastoral-sounding but later with a more Gallic accent. This is the first commercial recording of these songs and so contributes valuably to the Gipps discography (the recording of the Britten was the first in Sams’ translation, indcidentally). Indeed, there is just one catalogued instance of these songs being performed, some 70 years ago. Her melodic lines are also individual, and the interactions with piano (the piano’s little comments especially) are most engaging. Burnside offers a beautifully soft yet crystal clear tone. The noble serenity of the final song, “Peace, 1914” is particularly touching. A set of songs that most definitely rewards repeated listening, one hopes this also acts as a gateway to the exploration of the music of Ruth Gipps for many listeners.

There is, perhaps, something of a Britten-ish glow to the setting of Richard Lovelace (1618-1657), To Gratiana dancing and singing by W. Denis Browne (1888-1915). There is a real link to Rupert Brooke here: Browne was present at he moment of Brooke's death from septicaemia en route to Gallipli in 1915.; it was Browne who buried the poet on Skyros a few days later. Six weeks after that, Browne himself died at Gallipoli. Listen to the rolling piano chords of the opening. The song has a parenthesised “Pavan” after its title, and certainly one hears this in the music. The melismas of the vocal line are beautifully done by Llŷr Thomas. There are some lines that take in extremes of the tenor register, and Llŷr Thomas. traverses them with aplomb:

Michael Tippett’s Songs for Achilles (1961) follow, a song cycle by yet another composer known to have wrestled with his homosexuality. These find Llŷr Thomas joied by Craig Ogdon on guitar. One of the songs fom act 2 of Tippett’s opera King Priam (“Oh rich-soiled land,’ retitled as “In the Tent”; Tippett added two more. Teh premiere was by Peter Pears and Julian Bream. Llŷr Thomas clearly has a naural affinity for Tippett’s lines. I confess to some aversion to King Priam; a Covent Garden performance in 1985 left me unmoved; his melismatic writing has less potency than Britten’s, his contours are less memorable. No doubting Llŷr Thomas's ardent response, though, nor Craig Ogdon's evident virtuosity.

The final piece is the only one not to have texts reproduced in the booklet (for copyright reasons): Llŷr Thomas' own song-cycle for tenor and piano, Swan, setting o poems by Andrew McMillan, a gay English poet and lecturer, who was inspired by Sir Matthew Bourne’s famous all-male production of Swan Lake which depicted a human male falling for a male swan. There is the interesting aidea here of composing a deliberately 'operatic' voice into.a song-cycle. Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake is quoted at various points. The crystalline beauty of “the lake is calm tonight” cedes to the fluid textures of “my first time in water” (water is a constant throughout the cycle). Llŷr Thomas' harmonies are expressive, tonally-based but spicy. The sense of sepia-toned wonder in 'then the year everything was swan” is lovely; and no missing the Swan Lake quote opening the sixth song, “sing a swan of sixpence”. Most touching of all, perhaps, is the fragile final song, “I plucked each feather from myself”.

A superb disc that achieves everything its ets out to do - and so much more besides. Fine booklet notes by Lucy Walker and a brilliant, present recording by Paul Baxter seal the deal.

For those able to attend performances by Opera North, Llŷr Thomas will sing Prunier (Puccini La rondine) in October/November this year in Leeds, Newcastle upon Tyne, Nottingham and Salford Quays.

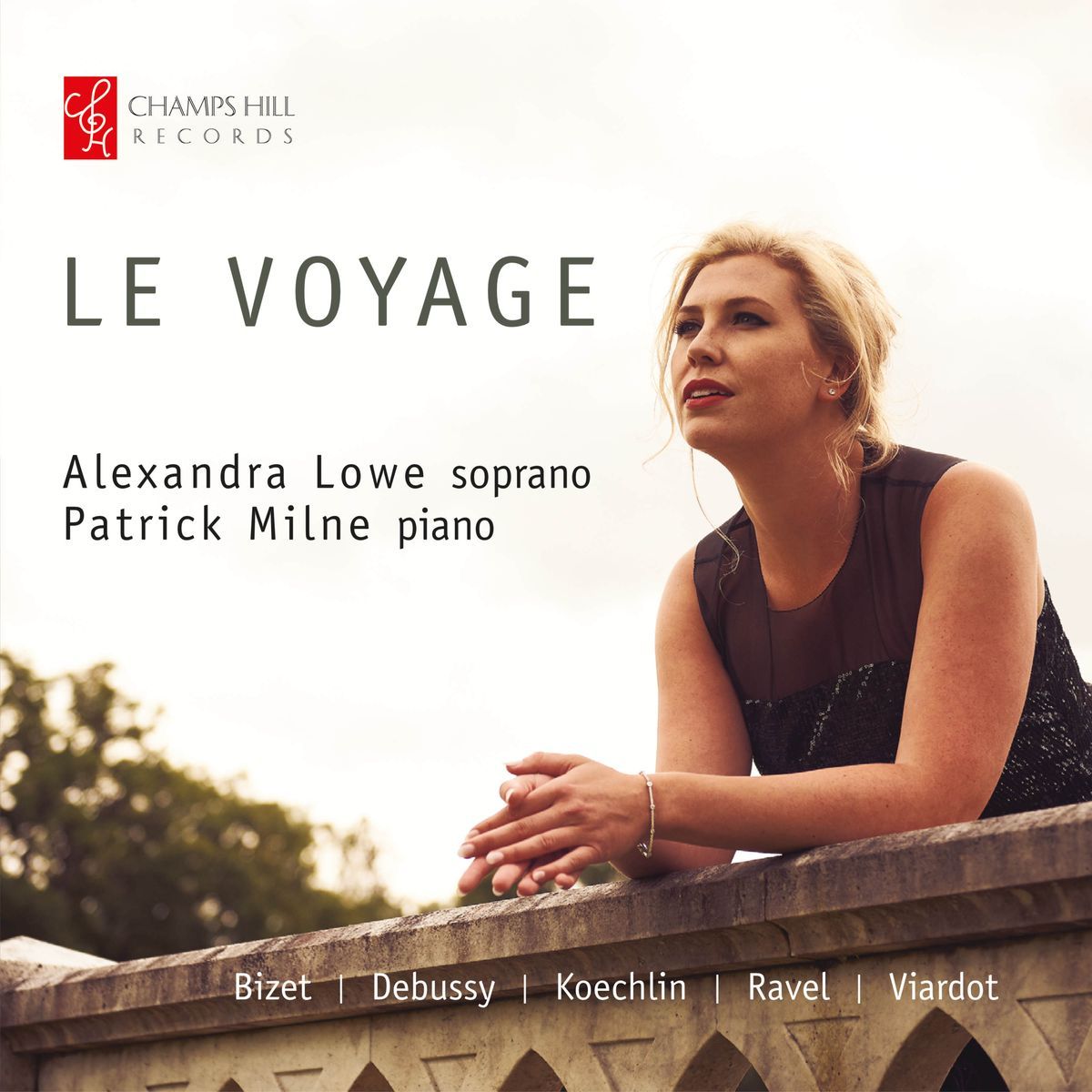

... and so across La Manche for French song by Spanish-born British soprano Alexandra Lowe, with pianist Patrick Milne. Lowe has impressed on a number of occasions, including Pappano’s Zauberflöte at Covent Garden (First Lady: review).

Here, in a disc dedicated to the late Dr Joyce Kennedy (1933-2021) who, alongside her husband, set up the Joyce and Michael Kennedy Award for the Singing of Strauss at the Royal Northern College of Music. Lowe won this prize in 2015, and it was at Joyce Kennedy's suggestion that this album was born on Champs Hill Records. Lowe has always been drawn to French song, and here she explores the influence of Greece, Spain and teh Middle East.

The performance of “Asie” from Ravel’s Shéhérazade sets the stall: languid, sultry but so controlled of voice and perfect of both pitch and of musical atmosphere, this is a superb account. Patrick Milne is just as fine, as he is in the sinewy lines of the second song, ‘La flûte enchantée’:

The sexual amiguities of text in the third and final song of Ravel’s piece “L’indifferent,” clearly link this to Llyr Thomas' disc. Slow, hypnotic, thsi is sweet seduction, gragrant, a shiwpered intimacy:

There is more to Bizet than Carmen and the L'Arlésienne Suites!. QED here, in the form of Adieux de l’hōtesse arabe, an 1860 song composed to a poem by Victor Hugo (from Les Orientales). A song of farewell, the final phrases contain an instruction to sing with sobs (Caruso would have loved it):

With the recent performances by Aziz Shokhakimov and the Strasbourg forces of Carmen, surely it is time to re-appraise Bizet? Here's a treat: a link to a video of the complete Symphony in C with the Orchestre National de la Radiodiffusion Française conducted by Thomas Beecham, a classic performance of a truly vibrant piece.

It's a nice idea to use that Bizet to separate two Shéhérazades, now set by Charles Koechlin as that composer’s Op. 84. A contemporary of Massenet and Fauré at the Paris Conservatoire, Koechlin’s music has gathered a small but devoted circle of admirers. It is ardent, passionate and harmonically a touch more explorative than that of his peers. He sets two poems not set by Ravel: try “Le chanson d’Ishak de Mossoul”:

It is a treat to return to Ravel in the form of his Cinq Mélodies popularies greques. Lowe's core vocal qualities are a fine soprano that is not too heavy and yet has body, making it perfect for this repertoire. Try the way she spins the line of the second song against Milne's ever so delicate traceries on piano pulls us into this song of fallen war heroes:

Lowe and Milne get the atmospherics just right, as they do in Debussy’s supreme masterpieves of song, the Chansons de Bilitis. These three songs seem to contain the very essence of Debussy, and need care lavished on them - just the care they receive from Lowe and Milne. Here’s the first, “La flûte de Pan”:

The exquisite song, “Le tombeau des Naiades,” is ravishing but also dolorous:

The recital ends with a sequence of five songs. Bizet’s Ouvre ton cœur is famous, and receives a fine performance. Note how Milne's repeated rhythm in the piano vibtrate with life, and how Lowe soars over it. And while the “Chanson espagnole” from the Chants populaires by Ravel is lovely, Lowe's enchantment is at its height in the vocalise (wordless song), the Vocalise-etude en forme de Habanera is pure magic (Lowe's lower range smoky and firm):

We have exolored Pauline Viardot here on Classical Explorer previously, both as composer and muse. Here we have two settings by Viardot of texts from Alfred de Musset's Voyage en Espagne (1845), the joyous Les filles de Cadiz, and the brilliantly inventive bolero, Madrid. Here’s the latter:

Two fabulous discs - fill your boots!