Verdi's Forza at Covent Garden .. and, in 1951, in Edinburgh

Verdi La forza del destino (1869 Milan version). Cast; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden / Sir Mark Elder. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, 19.09.2023.

Production:

Original director – Christof Loy

Associate director – Georg Zlabinger

Designer – Christian Schmidt

Lighting designer – Olaf Winter

Choreographer – Otto Pichler

Revival choreographer – Klevis Elmazaj

Dramaturg – Klaus Bertisch

Cast:

Leonora – Sondra Radvanovsky

Don Alvaro – Brian Jahde

Don Carlo di Vargas – Étienne Dupuis (replacing Igor Golavateno)

Padre Guardiano – Evgeny Stavionsky

Fra Melitone – Rodion Pogossov

Preziosilla – Vasilisa Berzhanskaya

Marquis of Calatrava – James Creswell

Curra – Chanée Curtis

Alcalde – Thomas D. Hopkinson

Maestro Trabuco – Carlo Bosi

Verdi’s La forza del destino is a work whose actions cover vast temporal spaces. After the first act (set near Sevfille), the second act moves on a year (and to Cordoba), while the third act is ‘years later’ than that (a military camp in Italy) then, for its second scene, three months later than that; finally, act four is in Spain ‘many years later’. Add to this the prequel mime director Christof Loy offers over the Overture – a story of abuse of three (not two) siblings, one of whom perishes – and it looks on paper like disparate pieces of a jigsaw. Neither is a ‘definitive’ score a clear-cut thing: Covent Garden uses the Milan score, its characteristics nicely elucidated in Jim Pritchard’s review of the 2009 production on Seen and Heard International here.

And yet, reframe this as various tableaux, and the piece can work. Certainly, Elder seemed to see it as such, painting each scene with a definite tinta, Loy’s set (designer Christian Schmidt) is constant throughout, with various symbols (Christ on the Cross for the monastery, for example) enabling changes of ‘locale’. And, riffing on Verdi and Piave/Ghislanzoni’s libretto (Antonio Ghislanzoni added text for the 1869 production), Loy continually references the past and past actions via projected video clips, visually distanced via black-and-white.

The Covent Garden orchestra were on brilliant form, ever responsive to Elder’s sure direction. His tempi seemed perfect – the four hours of the evening (two intervals, both of which seemed to keep to the promised 20 minutes) flying by. While there are moments of brightness (and how Loy revelled in tham, moving us close to vaudeville), the overall arc of the opera is from near-darkness to bleak darkness. The plight of the poor (and the religious establishment’s handling of them) pulled no punches. All of this is a massive balancing act for conductor and director: Loy and Elder offered a more than viable solution.

I see from the cast list of 2019 that it was a star-studded occasion, with Netrebko as Leonora, Ferrucio Furlanetto as Padre Guardiano, Alessandro Corbelli as Melitone and last but certainly not least, Robert Lloyd as the Marquis of Calatrava. That all sounds very yummy, but the cast on this occasion seemed remarkably unified in standard, and unified of intent, some thing that arguably counts for more.

The Donna Leonora here was Sondra Radvanovsky, dramatically compelling and in full control of her range (I had forgotten how well-formed her lower extensoin is). The way she spun the first 'Pace’ of the final act’s ’Pace, pace, mio Dio’ was heart-stopping. Matching her was Brian Jagde’s Don Alvaro, strong-voiced, heroic, her final cries of ‘Maledizione’ unforgettable. And matching Jagde was an assumption even more impressive as it was a stand-in (I would defy anyone to tell that on the basis of the stage action) - the Don Carlo di Vargas of Etienne Dupois (replacing Igor Golovatenko). Dupois has a phenomenally powerful, dark voice that is the perfect vocal foil to Jagde’s heroic tenor, and their scenes together (it’s fair to say they have beef) were of the highest Verdian standard.

The clerics were well cast. Evgeny Stavinsky was a solid Padre Guoardiano, Rodion Pogossov an equally convincing Fra Melitone. Carlo Bosi made much of the comedy-oriented part of Mastro Trabuco, and James Creswell had fine presence – both stage and vocal – as the Marquis of Calavatrava.

It is testament to the strength of fringe opera in London that for the character of Preziosilla, one can positively reference Regent Opera’s 2022 staging of Forza in Fulham, and its Preziosilla, Kamilla Dunstan, who was something of a force of nature. The Preziosilla here, Casila Berzhanskaya who, despite her decidedly international profile and the gift of Loy’s colourful staging, conveyed rather less of this character’s sass.

Few performances truly live and breathe the air of Verdi. It was a privilege to attend one that did. The insights from the pit just kept on coming. Split-second precision was married with some meltingly beautiful solo (too many to individually mention).

The combination of Loy’s insights (I am aware of other critical voices who may disagree!) and Elder’s own illuminations plus a cast that acted as a company rather than a constellation of stars was, on this particular evening, revelatory. If I had five stars, I’d give them

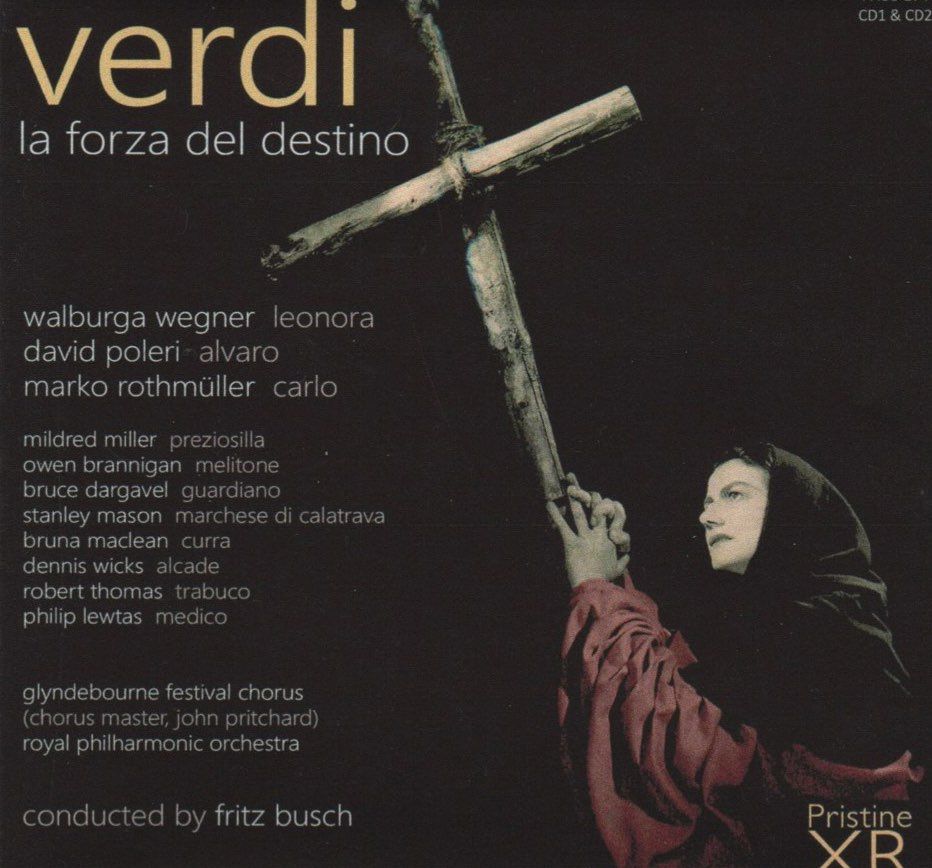

Part of the point of Classical Explorer is not to present the obvious. So, for all of the choice for a recorded Forza, let's go to a release by a fabulous company headed by one Andrew Rose, Pristine Classics, and a performance at Edinburgh by Glyndebourne forces (!) in 1951. There is a fascinating essay on the Pristine Classics page (linked below) that describes how Fritz Busch selected his Leonora (Walburga Wegner, 1908-93 and, in German in the Großes Sängerlexikon, Volume 4, here), the young American temor David Poleri (1921-67) and a singer best known for his seminal Britten performances, Owen Brannigan (as Melitone). Wonderful to see Mildred Miller as Preziosilla, too. Croatian baritone Marko Rothmüller is Don Carlo.

Although this YouTube of Wegner singing “Pace, pace mio Dio” is in less good sound than the Pristine Classical transfer (it is from an Andromeda set), it gives an idea of the compelling nature of her singing:

... but again, the star is the conductor: Busch is magnificent in his sensitivity to Verdi's scoring. Passages of arioso are markedly dramatic, yet disciplined. With generous Verdi fillers (orchestral excerots from Forza, Dresden 1926 and Chicago 1947), Pristine Classical’s set is well worth a listen.

This Pristine Classical performance can be purchased via this link in a variety of formats (MP3, FLAC, and physical) - full details of the performance are also available at that hyperlink also.