A tale of "two" operas: when is a Fidelio not a Fidelio?

So, when is a Fidelio not a Fidelio?: an updated post

[NB: This is an updating of an earlier post, to include brief comments (and a fascinating link) on the recently released 1805 Leonore released by Orfeo in March, 2021. The added text is at the end of the article]

So, when is a Fidelio not a Fidelio? The answer is not quite when it's a Leonore, as the more Beethovenianly-attuned readers might guess, although that is certainly true. Read on.

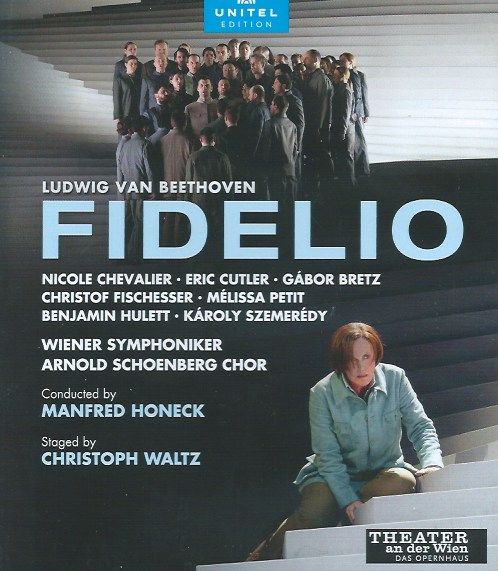

Beethoven's only opera was hard-won. Four overtures (Leonore I-III, Fidelio) is just the beginning. The first version dates from 1805, which did not have a good reception. It didn't help that Napoleon's troops were in Vienna. The revised version of 1806 forms the basis of Manfred Honeck's excellent performance. Although the two Blurays/DVDs featured today are of different versions of the opera, on a purely performance level the Honeck fares better. For that reason, we shall go in the direction of 1806 to 1805, from Vienna to Opera Lafayette.

Anyone who knows Beethoven's Fidelio in the final version we all know and love will have their eyes and ears opened as to Beethoven's working processes by these two performances. You might well cherish your Klemperer (either the famous HMV/EMI set or the Testament Covent Garden performance - the latter for some people even greater) but experiencing and seeing these two will immeasurably enhance your appreciation.

Last year - Beethoven year - there were to be performances across Vienna of all versions of Beethoven's opera; the 1806 version is particularly rare, and so the fact they put it on - albeit without audience - is a real triumph.

Oscar-winning Director Christoph Waltz opts for a neutral set of twisting, what looks like concrete staircases, an almost Escher-like, DNA-spiral installation in gray; costumes tend towards that same gray. Doing so really allows us to share the dynamics of the inter-personal relationships; and given the audience-less setting, the Theater an der Wien effectively became a film set. Lighting becomes vitally important - and is brilliantly, spectacularly managed - while the acting abilities of the cast, here way above the norm, becomes foregrounded. This opera, like the final version of Fidelio, is in two acts and, as we shall see, is already a substantially tightened version of the opera in comparison with the 1805 score. The whole is magisterially conducted by Manfred Honeck, who had previously impressed in Basel almost exactly a year ago with Seong-Jin Cho (see my recent Mozart post) in Beethoven's "Emperor" Concerto and Dvořák's Ninth Symphony.

The performance at Vienna's Theater an der Wien was broadcast on Austrian television; thence it went to medici.tv and now into the world at large via hard copy.

It begins with Beethoven's Leonore Overture No. 3 (Op. 72b); a virtual tone-poem that effectively summarises the action. Here, as everywhere, Honeck is in total control; his major achievement overall is to convey the 1806 score to us as a masterpiece; and certainly no second-best. It's fascinating to hear the differences: for example how Beethoven tightened up Pizarro's "Ha! Welch' ein Augenblick" (here the phenomenal Gábor Bretz).

This examination of different versions raises all sorts of questions. When Pizarro holds a knife to Florestan's throat, we hear the "altered" rhythms and ask ourselves, does it sound somewhat stilted because of what we're used to? After all, Beethoven produced a later version; and yet, he was never happy. And I have to say the area around "Töd' erst sein Weib" - the famous reveal of the male Fidelio as a woman, Leonore - is electric here, and one could easily argue it has the perfect amount of flow.

Honeck's cast is brilliant: Nicole Chevalier is not only a convincing man (I mean that with the utmost respect, obviously!); she conveys all of the grit and belief of the character. Eric Cutler is a fine Florestan, but almost trumping both is the supreme Marzelline of Mélissa Petit, who fits the role vocally, physically and dramatically like a glove. Honeck's conducting makes it, though: one is absolutely convinced this is a masterpiece, as opposed to a masterpiece-in-the-making. Honeck has the ansolute measure of the score from first to last.

Although absolutely no substitute for this physical release (the Bluray in particular boasts miraculous clarity), there is a YouTube video of the performance:

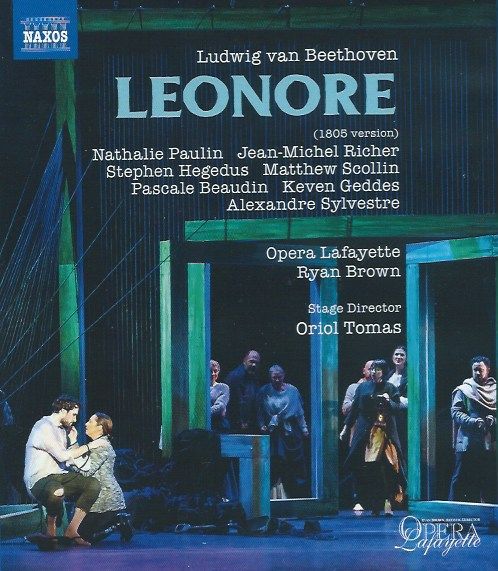

.... and so to the USA and Opera Lafayette, and their 1805 Leonore: the culmination of their "Leonore Project," celebrating not only Beethoven 250 but also Opera Lafayette 25 (their 25th anniversary, in other words).

This offers the first version, 1805; and it is Leonore Overture No. 2 that opens the performance, a valiant performance of fire. Authentic, crooked horns add rawness to the sound. I have only heard the 1805 version live once, in 2005 with COG (as it's affectionately known - Chelsea Opera Group) at the Queen Elizabeth Hall (review); so it is good to have it to hand.

The interested listener will be amazed at how stark the differences can be. The Vienna performance runs for 130 minutes; the Lafayette, 148 minutes. What is here act three, in particular, feels a lot longer than the final version of Fidelio. Differences are legion; dialogue is different, and we're in three acts not two (act 2 begins with the March; act 3 comes where we expect act 2, with Florestan's aria "In des Lebens Frühlingstagen").

And there's yet more!. Musicologist Will Crutchfield has reconstructed Florestan's aria at the beginning of the final act (that "In des Lebens") from sketches to give the first outing of the extended version, which includes Florestan's recollections in the first part of the aria and then a flute-led faster F major solo. Crutchfield goes into much detail in this New York Times article.

The staging, by Oriol Tomas, is sparse but functional; costumes are well chosen and again we have a convincingly male Leonore (Nathalie Paulin). Here's part of her "Komm, Hoffnung":

A mimed beating of a prisoner during the March that opens the second act sets the oppressive aura of what is to follow well; and Matthew Scollin is a nicely comic-book baddie as Don Pizarro.

French-Canadian soprano Pascale Beaudin and tenor Keven Geddes make for a fine pairing as Marzelline and Jaquino respectively. Their opening duet "Jetzt, Schönchen, jetzt sind wir allein" is delightful; it also forms the basis of this, the first in an eight-part series of approximately half-hour talks on Leonore, all of which are available on YouTube and make for fascinating background:

Jean-Michel Richer is a fine Florestan, absolutely believable in his extended final act aria; we palpably feel the depth of gratitude from Florestan and Leonore in their duet that leads into a chorus at "O Gott, welch' ein Augenblick" (a verbal mirror to Pzarro's earlier "Ha! Welch' ein Augenblick" of course).

Conductor Ryan Brown is fleet throughout, which keeps the drama moving (one wonders how long Klemperer might have taken with this version!); one might argue that the beauty of the miraculous "Es ist mir wunderbar" suffers a little from the velocity, but overall there is a trajectory here that becomes unstoppable.

A real company effort, this Lafayette Leonore offers another vital building block in our understanding of Beethoven. The musical differences between this and the Honeck Fidelio is perhaps best likened to that between English National Opera and the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in London. Both have strengths and weaknesses that complement each other, with ENO very much proud of its status as an "opera company" while Covent Garden boasts its global stars; and I for one would not be without either. Similarly, Lafayette comes into that integrated company bracket.

... and so to the addendum:

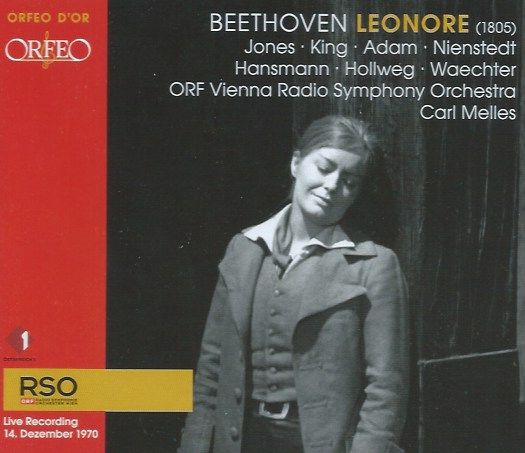

Conductor Carl Melles (born "Károly Melles" in Budapest in 1926; he died in 2004) is little-known today, so I'm delighted to offer this link to Christopher Howells' Musicweb International article on the Hungarian maestro in which Howells refers to this December 1970 live performance from the Musikverein in Vienna as "unofficially circulating". Unofficial no longer! Orfeo released it in a two-disc box on March 19, 2021.

In charge of the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra (quite a mouthful, even more so if one expands "ORF" to "Österreichischer Rundfunk"; Austrian Radio, in other words), Melles leads a finely-honed, lean account that builds to a very dramatically convincing close. Gwyneth Jones and James King were both known as their respective characters in the more familiar Fidelio; how good it is to have them in the 1805 score. The cast is replete with familiar names: Gerd Nienstedt as Rocco, the great Theo Adam as Don Pizarro and Eberhard Waechter as Don Fernando. While I am not fully taken by Rotraud Hansmann's Marzelline in the Act 1 Leonore duet with Jones' Leonore ""Um in der Ehe froh zu leben" (Hansmann's name might be familiar via Harnoncourt's early Bach Cantata recordings), the chorus, the Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien, is on absolutely top form. The second act Chorus of Prisoners a real high point, as is the full chorus cry of "Zu Rache" that initiates the third act finale. Both Jones and King are on cracking form (both are very strong-voiced and I fully appreciate both are known as an acquired taste). The recording, while clearly not to modern standards - it is taken from a radio broadcast, after all - is more than acceptable.

The Orfeo booklet includes a full German libretto .No translations, but supremely useful nonetheless. An invaluable addition to our picture of Leonore and Beethoven's journey to Fidelio. Here's the Overture: